When you watch the financial headlines, you rarely hear about the truly massive deals. While retail investors obsess over tick-by-tick movements on lit exchanges, institutions and high-net-worth individuals navigate a completely different infrastructure — one that exists in the shadows of conventional markets. The practice of executing enormous trades away from public view has become standard operating procedure across nearly every asset class, from equities to commodities to digital assets.

Beyond the Public Eye: How Large Trades Stay Hidden

The phenomenon extends well beyond traditional finance. When mainstream crypto holders plan to move into major positions, they route transactions frequently via specialized infrastructure instead of depositing funds directly onto public trading venues. Services such as a OTC crypto trading desk have become quite important to how institutional players handle their crypto exposure, enabling them to implement large orders without triggering the volatility and slippage that are intrinsic to the bulk trading on popular platforms. This is quite similar to the traditional practices in legacy markets where serious money navigates through purpose-built channels for execution quality and opacity.

The Basic Issue With Public Exchanges

Public exchanges work on a principle that looks good in theory but generate significant headaches in practice: price discovery via transparent matching of orders. Every trade appears in the order book, and every transaction gets recorded in real time. This transparency, while valued by regulators and smaller traders, introduces a specific problem when you're trying to move meaningful size: it broadcasts your intentions to every other participant in the market.

Imagine yourself as a portfolio manager who is accountable for hundreds of millions in equities. You must liquidate a mid-level position to generate funds for a new opportunity. On a public exchange, other traders look for your order patterns and identify that a persistent and large seller is in the market. That recognition triggers adverse selection — sophisticated trading algorithms begin positioning themselves to profit from your need to sell, widening spreads and pulling back bids just as you try to execute.

By the time you've completed a fraction of the sale, the price has already moved against you. That seemingly small difference — one percentage point on an eight-figure trade — translates into six-figure losses in execution cost alone. Scaled across a full year of rebalancing and reallocations, the aggregate cost becomes too large for serious institutions to ignore.

Information Leakage and Market Mechanics

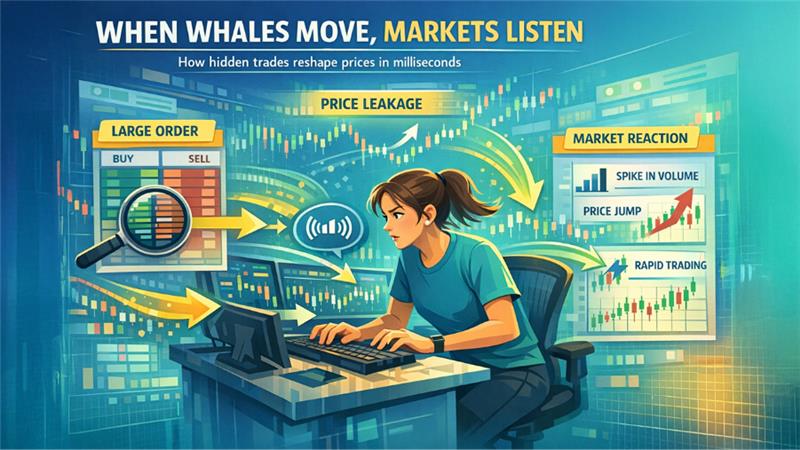

The challenge is not just the immediate price move but the way markets interpret information. Large orders appear rarely in a vacuum. A hedge fund closing in a major position can be seen as a signal related to future performance, just as a pension fund collecting stock in a sector can be seen as a strategic move on long-term fundamentals.

This signaling effect has been magnified by technology. Advanced trading platforms, from high-frequency organizations to execution algorithms utilized by large asset managers, consistently analyze order books for patterns that look similar to institutional flow. They infer urgency, estimate total size, and adjust their behavior accordingly, often within microseconds. For the institution trying to move size quietly, the environment has become structurally hostile.

Liquidity adds another layer of complexity. While major exchanges list deep volume on paper, the effective liquidity available at the best bid or offer at any moment is much thinner. When a genuine whale arrives in the market, visible liquidity can evaporate instantly, replaced by wider spreads and far less favorable prices. This fragility explains why visible order books are only part of the real liquidity landscape.

The Off-Exchange Solution

Off-exchange trading developed as a direct response to these structural issues. Instead of broadcasting intentions to the entire market, large participants work through brokers, internalizers, or private venues that match size discreetly. A portfolio manager can describe a desired trade to a block desk, and the desk can either commit capital itself or quietly line up natural counterparties.

In equities, this often takes the form of block trading desks at major banks or so‑called dark pools and bilateral off-exchange arrangements. In foreign exchange, much of the interbank market operates through dealer networks and request-for-quote systems that never touch the kind of public interfaces retail traders see. Commodities and futures markets also rely on negotiated block trades, executed away from the main order book but reported afterward within regulatory frameworks.

Time turns out to be a strategic variable. Major institutions can implement orders over an extended timeframe, i.e., over days or weeks, slicing implementation across counterparties and venues. Instead of having a single noticeable wave of buying or selling, the flow is gradually absorbed, minimizing both informational footprint and market impact.

Regulatory Framework and Compliance

Off-exchange does not mean off‑regulation. In most developed markets, large trades executed away from primary venues must still be reported, often with a short delay. That delay, typically on the order of minutes rather than milliseconds, is enough to mitigate immediate front‑running while still feeding aggregated data back into the broader price discovery process.

Regulators have wrestled with where to draw the line. The European Union’s MiFID II regime tightened rules on dark trading and capped some forms of off-exchange activity, pushing a higher share of flow back toward lit venues. In the United States, by contrast, off-exchange trading — including internalization and dark pools — has steadily risen and at times passed half of total equity volume, sparking debate about fairness and transparency.

Crypto markets sit in a more fragmented environment. Jurisdictional approaches vary greatly, while a few over the counter or block trading venues look for licenses and comply to strict AML and KYC regimes; others work under irregular or lighter oversight. Now, as the asset class matures more, regulators are greatly emphasizing such institutional implementation channels along with centralized exchanges.

The Volume Reality

The scale of off-exchange activity is hard to ignore. In U.S. equities, off-exchange and dark trading venues have reached the territory where roughly 40–50% of daily volume can occur away from traditional exchanges such as NYSE and Nasdaq. Europe shows lower but still substantial levels, with a significant minority of trades routed through alternative venues constrained by stricter caps.

Foreign exchange is even more skewed. The bulk of global FX volume moves through dealer-to-client and interdealer networks rather than through centralized order books. Corporate hedging, sovereign flows, and large asset-manager reallocations rely heavily on negotiated execution. For the end investor reading market news, the trades that shaped the day’s pricing often never appeared in a conventional public book.

The same pattern is emerging in digital assets. Institutional investors and large holders increasingly route size through OTC networks and desk-style services rather than spot exchanges whose visible depth would not comfortably absorb multi-million-dollar tickets. That parallel infrastructure is now considered standard for any serious participant in large-volume crypto trading.

Executing Without Moving the Market

Consider a global insurer with a multi‑billion‑dollar portfolio, including a large position in Japanese equities. A strategic shift calls for rotating part of that allocation into European assets. Trying to move that size directly through the Tokyo Stock Exchange order book in a short window would almost certainly drive prices meaningfully lower during execution.

Instead, the insurer engages a primary broker. That broker canvasses other institutions looking to increase exposure to Japan or reduce European holdings, effectively building a matching network around the proposed transition. Execution is broken into blocks, some transacted as crosses, some via off-exchange prints, and some carefully sliced into the lit market to blend in with normal flow. The final result is a completed rotation with far less market disturbance than a naive, exchange‑only strategy would produce.

In this kind of structure, each actor has clear incentives. The seller reduces impact costs, the buyers gain access to meaningful size at agreed prices, and intermediaries earn fees while reinforcing their role as central nodes in the liquidity network. None of this would function efficiently if every intention had to be declared in full, in real time, in a public venue.

Why Crypto Markets Developed Parallel Infrastructure

Digital asset markets have mirrored these developments with remarkable speed. Early crypto trading revolved around centralized exchanges where every order hit a public book, but once institutional capital entered, the familiar problem of information leakage and slippage reappeared. Large funds, family offices, and corporates found that broadcasting seven‑ or eight‑figure orders on a single exchange could move prices sharply against them.

As a result, dedicated OTC networks, bilateral desks, and specialized service providers emerged to handle large crypto tickets. Such setups ensure direct quotes, settlement procedures, and negotiated spreads personalized to size, often incorporating custody solutions and treasury platforms instead of retail-style exchange accounts. Managing crypto-based transactions effectively through these channels appeals to institutions seeking deeper liquidity, discretion, and more structured executions.

Stress events have emphasized the significance of this infrastructure. During the times of credit concerns or exchange turmoil, including mainstream failures in platforms, large holders have generally turned to OTC channels to handle risk, source liquidity, or restructure positions without causing visible cascades on public books. That behavior has strengthened the OTC layer as not a temporary but structural feature of the crypto environment.

Cost Structures and Execution Quality

Off-exchange execution rarely comes free, but its economics tend to favor large players. Instead of paying explicit exchange fees and suffering hidden impact costs, institutions negotiate spreads with counterparties willing to warehouse risk or find offsetting flow. The quoted price might sit slightly inside or outside the prevailing market, but when measured against the slippage avoided, total cost frequently ends up lower.

Execution quality in this context is multidimensional. It covers not just the final price but also fill certainty, settlement reliability, counterparty risk, and the ability to transact in size without telegraphing strategy. For many institutions, those factors collectively outweigh the simplicity of pushing everything through transparent order books, especially when mandates involve complex portfolios or regulatory constraints.

Time is especially important. Orders that would take days to work passively on a public venue can sometimes be completed far more quickly through a network of OTC counterparties. For firms responding to macro data, central bank decisions, or internal rebalancing windows, that speed becomes part of the value proposition.

The Transparency-Liquidity Tradeoff

Behind all of this lies a structural tradeoff. Public venues maximize transparency: everyone can see the same prices, quotes, and last trades. That openness supports price discovery and gives smaller participants confidence that they are operating on a level field.

Large trades, however, demand liquidity more than total visibility. Off-exchange mechanisms sacrifice some transparency at the moment of execution to preserve market stability and reduce the informational advantage of short‑term arbitrageurs over long‑horizon investors. Data still enters the system through post‑trade reporting and consolidated feeds, but in a way that blunts immediate predatory behavior.

Policymakers and market designers continue to debate where the balance should sit. Push everything on‑exchange and institutional execution quality deteriorates; allow too much in the dark and public price discovery may degrade. For now, the coexistence of lit markets and hidden liquidity pools remains the compromise underpinning how large-scale transactions actually move through modern financial systems.

Note: The blog has been written for informational purposes only. Users must consult all financial professionals and use their own discretion before making any investment decisions.